The Scientist: The Scientist:

Mike Grose BSc, BAntStud(Hons)

Institute of Antarctic and Southern Ocean Studies, School of Maths and Physics, University of Tasmania

Mike is currently in his first year of a PhD at the University of Tasmania and the Bureau of Meteorology looking at the biological production of natural greenhouse gases and ozone depleting gases in the ocean, and their release into the atmospheric system.

Mike, who was born in Hobart, has previously completed a degree in biological science, and then honours in Antarctic & Southern Ocean studies, where his project was looking at measuring productivity (photosynthesis) in the ocean using new technology.

After honours he participated in several marine science voyages to Antarctica, which he found really exciting and a great way to meet other scientists, and then started a Masters degree – a project on Antarctic sea ice. His masters work was used to make an improved estimate of the biomass of microscopic plants (algae) contained in the sea ice of the Australian Antarctic Territory.

“This is a very large amount of biomass, comparable to the massive forests of the world, and an important variable in the biological and chemical cycles of the world system,” Mike says.

After travelling for a couple of years overseas, Mike returned early this year with a renewed enthusiasm for science.

Mike was interested in science from an early age, and got involved through learning from enthusiastic teachers, reading science books and “taking an interest in the fascinating world of science history and research,” he says.

“All the previous work I have been involved with has happened through meeting science researchers, taking an interest in areas of science research and putting my hand up to become involved,” he says. “Through meeting people and cooperating with the exciting science community, opportunities to do interesting things become available.”

His current PhD work interests him for three reasons: firstly the opportunity to work on an interesting scientific question and discover things that have never been found before. Secondly, the chance to contribute to our knowledge about our world and climate which is very valuable to know as we head into the future, and thirdly, the chance to work with interesting and intelligent scientists in a challenging and stimulating environment.

“I find looking for answers to science questions very interesting and challenging, more of a goal and ambition than just a job,” he says.

“Working in science research can be very exciting because you can contribute to new ideas and help make new discoveries and help us understand our world. I really enjoy working on a project that has a long term goal of increasing our understanding and knowledge.”

More About the Work:

Key words: Phytoplankton, climate, atmosphere, ocean, methyl halides

Mike is studying gases important to our environment (in particular, methyl halides) and the microscopic plants in the oceans (phytoplankton) that produce them. This work involves having an understanding of the two key parts of our climate system – the atmosphere and the ocean.

The atmosphere viewed from space

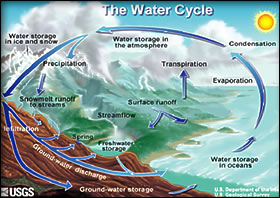

Reactions occur in both the atmosphere and the ocean – for example, in the atmosphere, the ozone cycle ensures a continuous supply of ozone to protect us from the harmful effects of ultraviolet radiation; and in the ocean, nutrient cycling is vital for all marine life. There are some cycles that occur between both the atmosphere and the ocean, such as the water cycle.

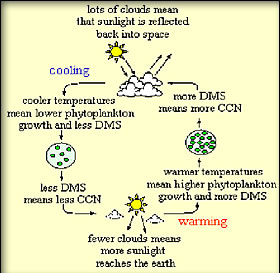

Other cycles involve the tiny plants, or phytoplankton, that live in the ocean. Certain species of these phytoplankton produce a gas known as dimethyl sulphide which is released into the atmosphere forming clouds. These clouds create shade, which means there is less light for these phytoplankton to grow leading to fewer phytoplankton and consequently less dimethyl sulphide produced, and so fewer clouds – all in one giant, ‘feedback loop’.

Mike is looking at the types of phytoplankton that produce other types of gases – namely, methyl halides, in particular:

Methyl bromide –

a gas that depletes ozone and is a greenhouse gas

Methyl chloride –

a gas that also depletes ozone

Methyl iodide –

a gas that depletes ozone and makes clouds (like dimethyl sulphide).

He will be taking measurements in the field of methyl halides in the air (at Cape Grim Baseline air Pollution Station) and in the sea and at the sea surface, as well as investigating phytoplankton ecology in coastal waters, and looking for correlations between the levels of methyl halides and the phytoplankton.

As well as looking at what is going on in nature, Michael will do controlled experiments in the laboratory, including measuring the production of methyl halides from phytoplankton grown in a sealed tank, and the enzymes in phytoplankton cells used in the production of methyl halides.

Websites:

Managing the Water Cycle

https://www.sydneywater.com.au/html/education/water_cycle/index.cfm

Water Science for Schools

https://wwwga.usgs.gov/edu/helptopics.html

The Ozone Hole Tour

https://www.atm.ch.cam.ac.uk/tour/part1.html

Understanding Ozone levels

https://www.atmosphere.mpg.de/enid/lb.html

Greenhouse Gases Online

https://www.ghgonline.org/carbondioxide.htm

Greenhouse Gas Lab

https://www.koshland-science-museum.org/teachers/postvgw-act008.jsp

Dimethyl Sulphide

https://www.co2science.org/subject/d/summaries/dms.htm

Gases from phytoplankton

https://www.atmosphere.mpg.de/enid/

e2c7ee356945cfd86d26f7d93ded8ac1,55a304092d09/1vj.html

Institute of Antarctic and Southern Ocean Studies

https://www.antcrc.utas.edu.au/iasos

|